5. Cartier's Second Voyage - 1535 to 1536

Jacques Cartier discovers the territory of Canada and Hochelaga

Updated: January 26, 2024

On the 19th of May 1535 CE, the winds were favorable in the port town of St. Malo, France. Captain Jacques Cartier ordered his sailors, companions, and specialists to board the three sailing vessels docked in the harbor. The King of France had covered the cost for the ships, sailors, and provisions. The largest vessel was the carrack Grande Hermine of 100 to 120 tons. The second largest was the carrack Petite Hermine of about sixty tons. The smallest was the bark Émerillon of about forty tons. Cartier was to command this little fleet, all seaworthy and manned with about one hundred experienced sailors.1

While the ships sat at the docks in St. Malo, the ship’s crews and dockworkers had been busy provisioning the ships for the upcoming expedition. They mended the sails and prepared them for sailing. They loaded barrels of gifts and trinkets, gunpowder and carefully wrapped weapons which they stored below decks. They distributed gallons of fresh water and tons of dried meats, fish, and biscuits amongst the ships. As the dockworkers loaded the ships, the sailors would start claiming bunks for the journey, while the officers brought into their rooms their equipment and supplies. Taignoagny and Domagaya (or as Cartier called him Dom Agaya) went onboard the Grande Hermine to assist Cartier navigate the unknown waters of Canada.

Taignoagny and Domagaya in France

Taignoagny and Domagaya became the first Indigenous people from Canada to experience Europe. This was the first intercultural exchange between the Indigenous peoples of Canada and Europeans, albeit reluctantly. No record is available of their experience of seeing French culture, but we can only imagine the utter shock of what these two young men must have gone through seeing a culture as alien as 16th century France.

Culture shock is a common human condition when anyone enters a new culture for the first time. Often this experience begins with fascination but eventually depression sets in as longing for the familiar becomes overwhelming. In time this dissipates as the foreigner accepts the new culture. For these two young men, the culture shock must have been extreme. Not only did they see European culture as completely alien and incomprehensible, but they also experienced a sense of being a constant focus of attention. The French people had never seen anyone like them. And except for Cartier and the sailors, the Iroquois visitors had never seen European towns, roads, buggies pulled by horses and enormous buildings containing the same totems (crosses) Cartier planted back home when they first met on the shores of the Great River.

Christian churches were completely unknown to them. These French people performed odd rituals in front of a dead man pinned to the same sort of totem Cartier had made back home. Why was a dead man attached to a totem? Why did they regard the apparent lord of these buildings as a king if the king is dead and attached to these totems? And how did they manage to use stone to make these buildings? Everything was new. It was all too much for them. Culture shock turned from astonishment to depression to loneliness. All they wanted was to return home to their people and their culture. And so, boarding the ship for home must have brought them an anticipation they had not felt for an exceedingly long time.

Once the sailors pulled the gangways into the ships, they got busy hoisting the sails. Wind filled the sails while the dockworkers loosed off the hawsers from the dock’s moorings. With favorable winds, the pilots directed the three ships down the river to the open ocean and pointed their bows west to the setting sun to start their journey. For Cartier, this was his second journey.

Sailing across the North Atlantic in the early 16th century was an act of faith. Taken on such a voyage had both recklessness and bravery we can scarcely imagine. The port of St. Malo to the eastern coast of Newfoundland was at least 2,000 nautical miles away and as the ships could sail at a rate of four knots, it would take five weeks for the three ships to cross at their quickest pace in good weather.

Cartier departs St. Malo on May 19th, 1534

On the 19th of May 1535 they set sail. Good sailing lasted less than a week into the voyage when on the 26th of May the weather turned sour. Strong headwinds, incessant rain and overcast sky persisted for weeks unleashing volumes of stomach contents overboard and earnest prayers for survival, each to their own gods. One can only imagine how Taignoagny and Domagaya feared for their lives hiding in the bowels of the ship being battered about as the ship tossed back and forth, not knowing if the next dip would continue its downward trend towards the great depths of the ocean.

It was not like they missed eating. That was the only relief they and the rest of the crew had. They did not want to eat the rotten, bug infested biscuits that squirmed inside the food barrels. Fear, hunger, stomach pains and more was the lot of 16th century sailing across open oceans.

To add to their misery, the storm caused the ships to become separated. The captains agreed to rendezvous within the Straight of Belle Isle once they reached Newfoundland. The Grande Hermine arrived first just off the Isle of Birds (Funk Island) on the eastern coast of Newfoundland. This was the 7th of July. Taking two long boats to the island, Cartier and his sailors filled their boats with birds to replenish their stocks. Cartier observes that the “island is so exceedingly full of birds that all the ships of France might load a cargo of them without perceiving that any had been removed.”2

Cartier’s observation shows how undisturbed the flora and fauna of the new world was. For thousands of years the Indigenous peoples took what they needed and no more. The Mi’kmaq, Iroquois, Innuit and Beothuk peoples thanks the plants and creatures they took for offering their lives so these peoples could live and thrive. Life was a continuum. They did not recognize a distinction between the human and animal worlds, or even between the non-animal worlds. Life had a multitude of forms, so they recognized other lives needed to perish for them to survive. And so, with reverence they took what they needed and no more. We can see in Cartier’s observation a radically different perception. This culture clash was about to lead to confrontation in a meaningful way soon.

Straight of Belle Isle - July 8, 1534

On the 8th of July, the Grande Hermine continued its voyage along the eastern and northern coastlines of Newfoundland until they reached the Bay of Castles (the Straight of Belle Isle, the waterway between Newfoundland and Labrador). This was the pre-arranged rendezvous point should they become separated, as mentioned. This location was well-known to the Basque fishermen who found a good harbor on the northern side of the straight. Cartier anchored there to wait for the other two ships. By the 26th of July, the two ships arrived whereupon they gave each other well deserved High-Fives to make the journey alive. For the next few days, they went ashore to refill their barrels of water, gather wood, repair the ships, and let their stomachs settle. Once ready, they began their journey into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Cartier had limited knowledge of the northern coastline but now they had two knowledgeable Iroquois guides who were keen on returning home and the captain hoped they would help him find that fabled route to China.

Things were looking up.

Cartier left a detailed record of landmarks the ships sailed past. So detailed were his records that centuries later we can trace on a map his exact route along the Labrador and Quebec coastlines. He frequently took soundings to determine the water’s depth and looked for hazardous shoals or rocks lurking underwater. He measured or sometimes estimated the width of waterways, distances between major landmarks and sailing times along the coasts. His unit of measurement was the nautical league which was approximately 3.5 miles. Cartier gave names to islands, harbors, rivers, capes, and points of land, unless they had existing Indigenous names which he adopted. Other locations he named after the inhabitants of the area. From time to time, he set up crosses on points, such as at Cape Thiennot (near present day Natashquan, Quebec) to help guide later captains on how to navigate the waters along the coast. Additionally, Cartier gave placenames based on a particular saint whose day it was when they discovered a landmark or waterway. One example is St. Lawrence Bay which he named after the eponymous Saint whose day it was when he arrived at this bay (now Pillage Bay).

Cartier discovers the St. Lawrence River

Sailing west, they coasted along what Cartier thought was a landmass. Taignoagny and Domagaya told them this land was an island (Anticosti Island). Cartier also learned that just beyond this island on the south lay Honguedo (Gaspé) where during his first voyage he captured them. As Cartier discussed a route with his Iroquois guides, he first heard a term that would eventually designate the second largest country on earth - Canada. He learned that “Canada” was the land along the northern coast of a great river that originated deep within the country.

However, to reach “the province of Canada” they needed to sail past the country of the Saguenay peoples who were most likely Inuit (Innu) whose lands stretched north to the Hudsons Bay. Having caught a favorable wind, they headed west until the winds forced towards the north shore. From a distance they saw "marvelous cliffs" but as the got closer, what they had seen were distant mountains. Nevertheless, the “savages”, as Cartier continued to call them, encouraged him to keep going west where the river would narrow and would lead them to Canada and to the “mouth of the great river Hochelaga”.3

Rather than continue west, Cartier turned east just to make sure he had not missed any significant river flowing from the north. Having satisfied that itch, he turned back west much to everyone’s relief. He did make one notable accomplishment on this side trip. He saw huge “horse fishes” many of which were found along a riverbank and in the water. The guides were quite aware of these creatures, which could exceed 4,000 pounds. They told Cartier they swam in the water during the day but at night lounged on the shoreline making lascivious noises and engaging in all sorts of boisterous acts. Today they are known as Walrus.

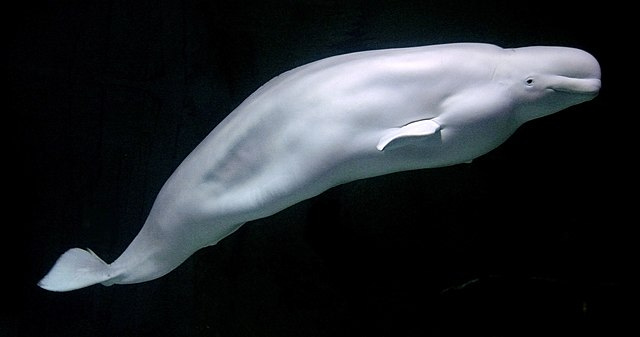

On the 3rd of September, they began their westward journey again to meet Donnacona and his people in Canada. Along the way they came across another wonder - a huge white fish without a back fin. Cartier wrote:4

“The fish was as large as a porpoise but has no fin. It is very similar to a greyhound about the body and is as white as snow, without a spot on it. Of these there are a very large number in this river, living between the salt and the fresh water”

What they saw was a large pod of what are known today as Beluga Whales. Cartier learned the Indigenous people caught them.

Ascending the St. Lawrence River to Canada

The Great River began to narrow while the water became brackish. Further on they paused near a village on the north shore called Tadoussac which was where the Saguenay River emptied into the Great River. Although this village was within the territory of the Innu peoples, it was frequently visited by the Mi'kmaq peoples who lived on the south shore of the Great River down to the Atlantic Ocean.

Just inside the mouth of the river, four boats rowed out to get a closer look at Cartier’s ships. They may have been coast guards from Canada on the lookout for threats arriving by boat. Having seen Cartier’s ships from afar, they perceived them as great creatures with white wings and getting larger as they came closer. Their dark hulls and white sails appeared as flying monsters who moved along the water. To their horror, these “creatures” sailed into the mouth of the river and stopped in the middle. Curiosity got the best of them, and the men ventured out to see what these things were. As they approached the ships, terror overcame them, and they began rowing away as fast as possible. However, Taignoagny and Domagaya called out to them. After hearing their own language, they turned back to get closer to the ships whereupon they Cartier invited them to come aboard and visit. Having done so, they met with their compatriots. Cartier did not record the conversations, yet it is easy to imagine what they must have thought about this experience as they rowed back to shore to speak about what they saw - humans and even relatives travelled in “great sea monsters.”

Later Taignoagny and Domagaya told Cartier that this small river was the entrance to the territory of the Saguenay peoples. He decided to take longboats to explore the river and to find where it ascended but finding the river narrowing and unlikely a river to China, he returned to his ships anchored off Tadoussac and set sail to continue up the Great River towards Canada.

They found the Great River hard sailing. Tides and swift currents worked against them and at one point they thought they might have lost their bark. The sailors rescued it by pulling it out. This little incident gives us an insight into just how tough and powerful these rowers and sailors were. Cartier had manned his expedition with tough sea-hardy sailors who had the wherewithal to even pull a bark out of a tight spot on a fast-flowing river.

Cartier reaches Canada on Sept. 7, 1534

Ascending the Great River, by the 8th of September, the three ships passed a string of islands (approximately fifteen islands, although Cartier counted only fourteen islands) which were on the south side of the river. This Cartier learned from Taignoagny that the territory of Canada began at these islands.

Hugging the northern side where the current made sailing easier, they approached a large island that formed like a “large plug” on this river with two fast moving small channels to the north and the south. Cartier named it “The Island of Orleans.” Here Cartier landed to meet the locals whom he had seen fishing near the island. At first, the locals fled in terror but when Taignoagny and Domagaya called out to them, they returned and began a greeting ceremony that Cartier described as “dancing and going through many ceremonies.”

Cartier does not record what this dance meant, how the St. Lawrence Iroquois performed it and what specific ceremonies they enacted. Even with his guides there to explain to him what was happening, Cartier does not record to his French audience what these rituals meant. He merely calls them dancing, shouting and ceremonies, meaning greetings of friendship. It is also quite possible he had no notion of their purpose.

Cartier does, however, mention the food offered to him and his fellow shipmates. For the St. Lawrence Iroquois, protein came primarily through freshwater fish caught in the St. Lawrence, such as eels, salmon, and other fish but land animals such as deer, bear and other animals caught in season. They also eat saltwater fish such as seal meat and other salt water. As well as hunters and fishermen, they were also successful agriculturalists. They eat corn from which they make baked bread. Cartier observed that as the French eat wheat as their staple grain, the Indigenous eat their corn. They also grew “large melons” which were squash, and they grew beans that along with corn was the Three Sisters of the Iroquois peoples. Cartier mentions Île d'Orléans had vines, grape vines. At first, I seemed skeptical that vines could exist there, and that Cartier was mistaken but today vineyards can be found just south of Quebec City. The French would know about vineyards, so clearly wild grapes grew in the area. But it does appear the inhabitants had no knowledge of maintaining vineyards, nor did they really need to know. Vines grew quite well in the area (snow was no barrier to their growth, just deep cold). All they needed to do was harvest them from when they were in season and September was harvest time for grapes.

While Cartier and his men toured the island, he noticed no permanent settlement but only huts. The Indigenous people he met offered Cartier gifts of food, whereupon the captain returned the favor by giving them small trinkets as gifts.

After Cartier returned to his ship, hundreds of men and women in boats approached the ships from the mainland to get a closer look.

Cartier meets Donnacona - September 8, 1534

The next day, on the 8th of August, Donnacona the Lord of Canada (as Cartier called him), whom the people called Agouhanna, came with twelve boats to approach the ships. Ten boats remained stayed back while two boats with sixteen men and Donnacona approached the bark Émerillon. The Lord of Canada began a long-animated speech to signify a welcoming ritual. They continued to the Petite Hermine where he spoke the same words. When they arrived at Cartier’s ship, the Grande Hermine, Donnacona began to speak directly to Taignoagny and Domagaya in their native language.

The two men spoke about the land they visited, how they were treated and how glad they were to be back with their own people. The record seems to suggest the two had a vacation in another land with good accommodation, decent food, activities and sightseeing to keep them busy. However, based on how Taignoagny and Domagaya regarded Cartier and his ships later, I am sure it was less than pleasant in France. They were like acts in a circus with people lining up to see these “savages” from the new world. Anyone treated that way would endure a gut-wrenching longing for home which must have run deep.

As Donnacona returned to his boat, Taignoagny and Domagaya took leave of Cartier and entered Donnacona’s boat to return to their people. Cartier then ordered his ships to be anchored just inside the mouth of the St. Croix River. This was a small river heading north, while the Great River, although very narrow at this point headed west. At the intersection of these rivers was the St. Lawrence Iroquoian village of Stadacona, the home of Donnacona, Taignoagny and Domagaya and hundreds of others.

Goodwill existed between Cartier and Donnacona, but it would not be long before this goodwill would be tested. Two key factors would lead to this. The initial distrust was French habit of always wearing weapons but the dealbreaker was Cartier’s plan to go to Hochelaga, a rival village up near the source of the Great River. We will uncover the reasons and consequences in my next article.

What does Canada mean?

Heritage Canada’s short video about Jacques Cartier shows Donnacona welcoming Cartier and his sailors to his village. According to this video, after Cartier asks where they live, the great chief says in his native language “Canada,” or “Kannata.” Cartier understand Canada to mean the country, while a subordinate mumbles, “I think he meant Canada is the name of his village.” This little vignette demonstrates disagreement about the meaning of Canada.

Why such divergent views about the meaning of the word Canada? In “The Voyages of Jacques Cartier,” a footnote gives Canada to mean a village. For example, James Baxter’s translation in 1905 gives this:

There can be no doubt that the word Canada is derived from cannata or kannata which in Iroquois signifies a collection of dwellings, in other words a settlement, and it is probable that when the Indians were asked by the French the name of their country, they replied, pointing to their dwellings, ""Cannata," which their interrogators applied in a broader sense than was intended.

On the other hand, Ramsay Cook, who worked for Archives Canada, has in his 1924 translation has the following:

As will be observed farther on, this word is always used to designate the region along the St. Lawrence from Grosse Island on the east to a point between Quebec and Three Rivers on the west. It is so represented on the Vallard and Carcator maps and on the Hakluyt's map of 1589....The modern Mohawk form is Kanata.

What about Cartier himself? Cartier wrote:

On [Tuesday], the seventh of the month (September 1536), being our Lady’s Day, after hearing mass, we set out from this [Coudres] island to proceed up stream and came to fourteen islands which lay some seven or eight leagues beyond Coudres Island. This is where the province and territory of Canada begins.

If we look at a modern map of the area, Quebec City is in the center of this territory. On the upper right is Coudres Island. On the lower-left is Trois-Rivières (Three Rivers). This was the land Cartier understood to be Canada.

Cartier provided a lexicon of St. Lawrence Iroquois words. In the French he writes “Ilz appellent une ville,” which he translates from the Iroquois “Canada,” the word the inhabitants use for “Village” which suggests Baxter was correct in his understanding. However, the English word “Home” can also be used for a village, a town, even a country. For these people, their home, their village was, Canada that consisted of territories on the north shore of the Great River from just beyond Coudres Island to a point between Quebec and Trois-Rivières. And as the Indigenous peoples moved their villages to better locations after the soil became infertile from intensive farming, it makes more sense to consider Canada as a territory not a particular set of dwellings in one location.

In the next installment, Cartier travels upriver to a larger village Hochelaga, against the wishes of Donnacona, greatly testing the trust between the French captain the the Lord of Canada.

For further reading, see: “The Voyages of Jacques Cartier with an introduction by Ramsay Cook” and “The Memoirs of Jacques Cartier” by James Baxter.

Cook, R. The Voyages of Jacques Cartier with an Introduction with Ramsay Cook, (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1993), 40.

This was the name Cartier gave to the St. Lawrence river. See Clark, Voyages of Jacques Cartier, footnote 66.

Cook, Voyages of Jacques Cartier, 48.

Glenn- So many great details here that I'm learning, especially: "While Cartier and his men toured the island, he noticed no permanent settlement but only huts. The Indigenous people he met offered Cartier gifts of food, whereupon the captain returned the favor by giving them small trinkets as gifts." This seems to me like something that really zooms into their life at sea and on land, and rings true. I appreciate the insights. Hope you're well this week? Cheers, -Thalia