IV. Michael Servetus and the Polish Brethren

The time to replace superstition with rational thinking arrived in Geneva via Italy and then to Poland.

Anabaptism

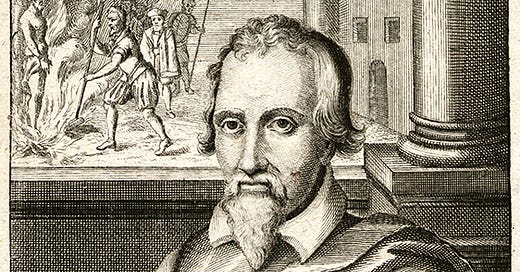

In my previous article III. Why did Calvin execute Servetus, I attempted to explain how one of the key Reformers behaved so inconsistently with his own values by causing Michael Servetus to be executed. We know, of course, Servetus was executed twice – first by Catholic authorities in France during 1553 then again by Calvinist Genevan authorities in 1553. The former did little damage to him. His effigy went up in flames. The latter did him in.

At least he was given the dignified execution for heretics by being burned alive at a stake, to, I suppose, give him time to repent.

Both John Calvin and the French Catholics denounced Servetus for believing and promoting a heresy. Michael Servetus had wrote a series of books that described a view of the Trinity and baptism that outraged them. (He rejected the Trinity and argued only adults can be baptized.) Yet Catholics and Calvinists were primed to look out for any signs of heresies, especially John Calvin. He had been dealing aggressively for the past twenty years with any Anabaptists that came within his jurisdiction.

Anabaptism means “Rebaptiser”, which is a label given to those who promoted adult baptism. To Calvin, Luther, Catholics and others meant they were rebaptized after having their first baptism as an infant. In fact, Anabaptism was making many converts amongst peasants, priests and tradesmen in Catholic and Protestant lands.

Calvin was worried about this and for good reason. He felt pressure from Papal and Imperial authorities who were dealing with the inroads of the Ottoman armies on the eastern edges of the Holy Roman Empire. Hence, Calvin wanted to keep the Imperial Christian powers passive - at least in areas that adopted Calvinism. He needed to be seen to be dealing effectively with Christian heretics. Servetus ended up dead to prove Calvin was doing just that.

In this article, I want to show that despite the best efforts of Calvin and the Catholics, Michael Servetus managed to influence an entirely new branch of Anabaptism. These were a group of like-minded individuals who came to be known as The Polish Brethren, or informally, the Socinians. They believed in adult baptism but also forms of antitrinitarianism (a novel approach to defining the relationships between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit).

You might ask how did Servetus end up influencing the development of Socinianism?1

Even if you didn’t ask this, it is worth understanding the dynamics of Europe during an era where new lands were being discovered almost yearly; old political and religious boundaries were constantly changing; and rulers were struggling to contain forces well beyond their controls on both sides. Into this mix the Anabaptists seem to represent an existential threat to the Christian order and they had to be dealt with.

Servetus’ execution stirred the consciences of an intellectual cadre of Italians who already had become refugees in their own lands in Northern Italy. A group of reform minded intellectuals fled the Inquisition in Italy and came to Geneva expecting a receptive welcome only to learn one of their own like-minded reformers was burned at the stake. It was very unsettling. Not finding a place of refuge in Geneva, many of them made their way to Poland and joined a group already in development there – the Polish Brethren - and quickly became the leading teachers and promotors of the Polish Brethren.

This new Anabaptist movement, though short lived during the 16th Century, would go on and influence some of the greatest English thinkers, including Sir Isaac Newton and become the origin story of a prominent group of people today who call themselves Unitarians.

The Polish Brethren were mainly known for replacing superstition and mysticism in favour of Rationalism. And it was the Italian converts who were primarily responsible for this mindset. They are worth learning about.

Who were the Polish Brethren?

Before considering the influence of the Italian Reformers, let’s consider the origins of the Polish Brethren.

The Polish Brethren were an obscure sixteenth century religious movement, but that should not be surprising. Suppressed movements present certain challenges for historians. Any attempts to suppress usually results in our own source of information about a person or group coming from their enemies. Fortunately, the Polish Brethren had amongst them people who were eager to document their origins, practices and theology.

During the 1550s, before Servetus was executed, a Reformed Church patterned after Calvin’s church in Geneva had developed in Poland, mostly in the Krakow area. Calvin was quite aware of the spread of his teachings there. According to noted Unitarian historian E. M. Wilbur, the Reformed Church was reforming further than Calvin wanted it to go and this included calling into question Trinitarianism.

Supposedly, the origin of the Polish Brethren had been dated to the execution of a heretical noble woman, Katherine Weigel, on April 19, 1539.2

However, according to Wilbur, the beginning of the Polish Brethren occured in 1546 at a dinner meeting in Krakow, Poland. Guests at the home of a certain pupil of Erasmus called Jan Trzycieski wandered into his library to pass the time and began, as most people would, look at the host’s book collection. One of the guests oddly called Spiritus who was a Dutchman picked up a prayer book and started reading it. After a while something on a page popped out at him. He looked at the text then wondered out-load why some prayers were “addressed to God the Father, some to God the Son, and some to God the Holy Spirit”. He then asked,

“Why do we pray to three distinct beings?”3

Of course this got all the guests giving their inputs into this unexpected topic. Each guest offered their opinions but none satisfied Spiritus. The topic caused them to feel a bit uneasy, if not blindsided by the suggested answers. What, they all wondered aloud, had they been taught about the nature of God. However, nothing further came of this question. Perhaps it had happened a thousand times in the past without anything coming of it. The usual response to these type of questions was to ignore the off-balanced feeling and get on with life.

But in January 1556 during the opening at the Synod of Secemin4 which had been called to consider certain Calvinist church reforms in Poland, the issue of the Trinity broke out into the open again. But this time it became a topic at the conference with arguments raging on both sides of the debate.

When Petrus Gonesius, otherwise known as Peter Giezek4, presented his views at the synod they were considered blasphemous and heretical, mostly because they were antitrinitarian. Just as in Geneva, Switzerland, so in Secemin, Poland, the Trinity became a topic.

This was the first open incident of antitrinitarianism in Poland. It began a long troublesome debate in the Polish Calvinist Church that eventually led to a schism in the church. One group advocated a strict Calvinism in all of its teachings which other group could not agree to.

This schism eventually led to two Calvinist-related churches. The larger group, which were the strict Calvinists, became known as the Polish Major Church, while the smaller group, although not completely rejecting Calvinism, became known as the Polish Minor Church. It was this smaller group that adopted an antitrinitarianism5 position which the larger church could not agree to.

Enter Michael Servetus

So, what was Michael Servetus’ role in all this?

We may not have known about Michael Servetus as a Spanish theologian until Calvin forced him onto the pages of history. It is quite possible we may only have known about him in medical textbooks. While living in Paris, he worked as a physician and began a search in the body for the source of its animating spirit. It was during this time that he described the Pulmonary Circulation of the Blood during his search for the soul in the human body. This for the layperson is somehow related to the blood flow through the blood flow exchanges gases and so forth between the lunges, heart and so forth. Imagine it like the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in leaves that keeps a tree alive.

This caused little controversy and entered medical history. His theological teachings, on the other hand, encountered stiff resistance. However, when Calvin burst Michael Servetus onto the public stage, it was Calvin and not Servetus that was criticized. Calvin’s intolerance for theological differences caused many to reconsider Calvin as a Reformer and set in motion the Religious Toleration Movement. In fact, this may have become Servetus’ greatest legacy.

But in a clear second place was his legacy influencing the Polish Minor Church.

Rationalism replaces superstition

Superstitions were the operating mind-set of European society up to and including the 16th century. Breaking through this required a certain courage few had. For example, sailors heading out into the Atlantic heard tales of monsters and so few were willing to venture far from shore. Those who had the courage discovered vast new lands soon to be named the Americas.

Similarly, European scientists of the 16th and 17th Centuries were attempting to discover the workings of the natural world without drawing on superstition. But for the religious-minded, few dared to venture far from their comfort zones of superstitions.

Servetus and the Polish Brethren stepped out of their comfort zones and redefined some fundamental Christian teachings such as baptism and the relationship between the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. And for that they were persecuted and forced to flee to safer lands, if they escaped executions.6

Italian humanists and the Polish Brethren

Fleeing the Inquisition in Italy, Italian protestant humanists gathered in the Italian Churches at Geneva and at Zurich.

While in Switerland, they head about the execution of Servetus. This caused Italian exiles to ponder about the apparent problems they saw in the orthodox view of the Trinity in the light of Servetus’ views. Many would make their way to Poland and join the Polish Minor Church, now known as the Polish Brethren.

Of all the Italians, none affected the Polish Brethren more than Lelio Francesco Maria Sozzini and his nephew Faustus Socinius.

What the Polish Brethren needed was someone to rigorously define their theology. Until the Italians began arriving in the Polish Minor Church, their doctrines were ill-defined. They all had a general agreement about what they believed but they needed someone who could rationally define who they were. Faustus Socinius became that person and his famous work - The Rakovian Catechism - formulated for future generations their doctrinal positions. Its unique approach was its appeal to reason not to superstition and it became an attractive alternative to scientists who were doing the same thing but for the natural world.

We visit Faustus Socinius in upcoming articles.

Swiss Anabaptists and the Italian humanists

Ulrich Zwingli, the leader of the Reformers in Zurich, Switzerland, had exiled any Anabaptists (those who practiced adult baptism) living within the canton of Zurich (after some public burnings and drownings). Most went to South Germany or Austria, but some ventured to northern Italy and settled amongst Italian Humanist circles.

Not all these Anabaptists who went to Italy had antitrinitarian leanings but among them were those who were influenced by Servetus’ criticisms of the doctrine of the Trinity and the deity of Christ.7 While in Italy these Servetan Anabaptists influenced some of the Italian Humanists with Servetian thought. Writing about these Italian converts, Wilbur writes

They were all Italian Humanists who under the influence of the early Reformation had abandoned the dogmas of the Roman Church, and who, especially in the north of Italy where the influence of Servetus was wide-spread, proceeded, independently of the guidance of Luther and Calvin, to think out for themselves a liberal biblical theology.8

These Swiss Anabaptists in Italy eventually gravitated towards the liberal-leaning humanists. A leading propagandist of Protestant thinking in which the Anabaptists circulated was the Spaniard Juan Valdes (1490-1541) who was well known in Rome for his criticisms of Church corruption. In Naples he gathered about him many liberal thinkers, the most significant was the Friar Bernardino Ochino “who has also been reckoned as perhaps the most influential propagator of the Protestant doctrine in Italy”.9

Bernardino Ochino (1487–1564)

The Italian Inquisition caused many Italian liberal thinkers to head north and settle in the Reformed lands, especially Geneva. This included the Friar Bernardo Ochino of Siena. Once in sufficient numbers in Geneva, they established the Italian Protestant Church. The most refugee was was the friar .

Bernadino Ochino (1487–1564) had the distinction of being the first to be summoned before the Italian Inquisition in Rome for his alleged Lutheran views.10 However, before the Italian authorities could arrest him, he fled over the Alps to Geneva where he was warmly welcomed in the Italian Protestant Church. While in Geneva, he did not publicly say anything that would have implicated him with antitrinitarianism. But later when the Servetian affair broke out in 1553 he publicly expressed sympathies that were clearly pro-Servetian.

Later, Ochino was given a post as preacher at the Italian Protestant church in Augsburg but had to flee due to pressure from Catholic authorities. He found a welcome home in England under the Protestant King Edward VI but had to flee once more when Queen Mary imposed her bloody purge of Lutherans and Calvinists. He returned to Zurich where he became the preacher to the Italian exiles there. He worked with other Italians, including Leilo Sozzini, who had recently moved there.

After the death of Servetus in 1553, Servetus’ thinking was “smoldering” in Zurich during the time of Ochino’s leadership of the Italian Protestant Church in that city.11

While in Zurich, Ochino wrote against the Trinity and it seems quite reasonable to conclude that Leilo Sozzini had influenced him on that matter. This resulted in banishment and exile once more but this time Ochino made his way to Poland, already known as a refuge for Protestant exiles from across Europe.

Here he joined with other dissidents within the Polish Brethren. However, in a few years he would have to flee once more as the Polish authorities ordered all foreign dissidents to leave on pain of death. He but succumbed to exhaustion and the plague while fleeing Poland. He died in Moravia a broken and penniless man. His children would also suffer, three of whom would die of the plague.

Professor Matteo Gribaldi (1505 – 1564)

Back in Italy the writings of Servetus were gaining traction. A few years earlier in 1550 an Italian legal scholar by the name of Matteo Gribaldi of Padua (1505 – 1564) obtained a copy of Servetus’ defining work The Erroribus. Gribaldi didn’t agree with all that Servetus wrote but this treatise shifted his opinions on the Trinity away from Orthodoxy to a more antitrinitarian approach.

Professor Matteo Gribaldi had an estate in the village of Farges, France not far from Geneva. During 1553 while at his estate he heard about the trial of Servetus so he decided to see the trial for himself. Like Ochino, Gribaldi was deeply disturbed by the whole proceedings. He felt that no one should be punished for their beliefs. He eventually left Geneva to return to Padua before Servetus was executed.

On his way he visited various Swiss congregations and tried to persuade them to tolerate dissenters. Back in Italy, he hosted Lelio Sozzini who he may have met while in Zurich. Sozzini had returned to Italy and was welcomed into the Gribaldi household. Over dinner or during walks around his Italian estate, they shared their views about the events in Geneva and had realized they they were of one-mind on the matter. This would encourage both of them and they determined to teach their views on the matter at any opportunity.

Back at his teaching position at the University of Padua, he convinced a number of Polish students to reconsider the Orthodox Trinity in favour of an antitrinitarian position. Later in 1554, Gribaldi took up a teaching post at a university in Tübingen. He must have had a lasting effect on his Polish students as they joined him there.

Gribaldi and his little group of Polish students passed through to Geneva on the way to Tübingen. While there they attended the Italian Protestant Church. Surprisingly, the issue of the Trinity had become a point of discussion. Gribaldi’s input into the debate12, which was misunderstood as Tritheism, gave support to the antitrinitarian viewpoint. But the issue was inconclusively settled and Gribaldi decided to leave Geneva but not before Calvin attempted to bring him before the Genevan authorities. But the city council decided to let him leave the city because as an Italian he was not under the jurisdiction of Genevan law.

Before leaving Geneva he was given a copy of Servetus’ Two Treatises. Its effect on him was that

“without which he afterwards declared that he should never have known Christ”.13

He left Geneva but trouble lay ahead. Someone attempted to assassinate him while on the way and then when he arrived in Tübingen, he learned that he had lost his teaching position. His estate in France was then confiscated by French authorities and he was constantly under suspicion for holding “pernicious” views. He petitioned to have his estate reinstated which was granted to him on certain conditions.

The remainder of his life would be one problem followed by another. Eventually, the plague took his life in 1563. But he convinced his Polish students to accept his modified Servetan views on antitrinitarianism, which they brought with them when they joined the Polish Minor Church.

Professor Matteo Gribaldi’s views on antitrinitarianism was not entirely Servetian nor was entirely the views of the Polish Brethren (later to be known as Socinianism). But it was Gribaldi’s teachings which Wilbur considered as

one of the “bridge(s) between Servetus and the beginnings of what was soon to develop into the Socinian movement in Poland.”14

Dr. Giovanni Giorgio Biandrata (1515 – 1588)

Another Italian Protestant refugee was the physician Dr. Giovanni Giorgio Biandrata (1515 – 1588).

Like Ochino, Dr. Giorgio Biandrata fled the Inquisition in 1556 with other like-minded Italians and came to Geneva where he joined the Italian Congregation. The execution of Servetus was still on the minds of the Italian Reformers there and eventually began to influence the thinking of Biandrata. It seems the fallout from Calvin’s execution of Servetus caused more people consider Servetian thinking on the nature of the Godhead rather than snuff it out.

While in Geneva, Biandrata became a leader of the Italian Church and came under the influence of Professor Matteo Gribaldi. Biandrata began to question the divinity of Christ and he talked about it to anyone would hear, even to Calvin. This was too much for Calvin. Fearing for his life, Biandrata left Geneva in 1558 for Poland to join the Polish Minor Church.

While in Poland, he attempted to encourage the members of the Polish Major and Minor Churches to tolerate a range of Protestant beliefs. In this he was only moderately successful so he decided to move to Transylvania. He became court physician to King John Sigismund of Transylvania where the court preacher and former Bishop Ferenc Dávid fell under Biandrata’s influence.

Biandrata owned a rare copy of Servetus’ Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity) and with this treatise he successfully convinced the King to adopt a form of antitrinitarianism. He also discussed with the King the importance of religious tolerance, the same message he gave in Poland. Eventually, this led to the The Act of Religious Freedom and Conscience by King John, the first such declaration in Europe.

Although not a significant influence upon the Polish Brethren, his contributions would become another step towards a more “mature thinking” of the Polish Brethren.

Dr. Giovanni Alciati (1515– 1573) and Giovanni Gentile (1520 – 1566)

Other Italian Reformers also joined the trek to Poland including a wealthy nobleman of Piedmont with an impressive sounding name - Dr. Giovanni Paolo Alciati della Motta (1515– 1573).

Like Biandrata, Dr. Alciati was an Italian physician and a Calvinist who embraced antitrinitarianism. In 1546 he moved to Geneva to run a business. While there he joined the Italian Congregation. And like Gribaldi, he objected to the trial and execution of Servetus. Falling foul of Calvin’s confession test (a theological test based on Calvinism), he was forced to leave Geneva but travelled only as far as Zurich. However, thinking better of his decision, he chose to return to Geneva “hoping to save his business interests there”. However, he was unable to recover his business so he decided to join the Italian exiles in Poland at the invitation of Dr. Biandrata.

Giovanni Valentino Gentile (1520 – 1566), like many of the Italian Reformers, had been influenced by Juan de Valdés. As he could not stay in Italy due to the Italian Inquisition, he went to Geneva and joined the Italian Congregation. While there he travelled to France to visit Matteo Gribaldi at his estate. At the time Gribaldi was hosting Dr. Alciati before the Physician had made his departure to Poland. Gribaldi’s estate had become a hotbed of antitrinitarianism as Alciati, Gribaldi and Gentile15 shared their views with anyone who would listen.

Eventually Gentile joined Alciati in Poland and joined the Polish Brethren. Unfortunately for Gentile, Polish authorities forced him to leave Poland after being accused as a heretic. Finding his way to Bern, Switzerland, Gentile experienced the same fate as Michael Servetus when the Calvinists in Bern, a city east of Geneva, had him burned at the stake.16

Francesco Stancaro (1501 – 1574)

Gentile’s and Alciati’s main contribution to the Polish Brethren was in making a leading antitrinitarian in Poland, the Italian exile Francesco Stancaro more “heretical” than he was.

Francesco Stancaro (1501 – 1574) was originally a Catholic priest in Poland who held antitrinitarian views. He went to Italy to teach at the University of Padua and while there came under the influence of reformist idea. His oratorial skills, scholarship and knowledge of Hebrew allowed him to become a Professor of Hebrew. Back in Poland he become very influential in the Protestant reform circles in Poland, including the aristocracy.

He “was one of the most successful people who had worked to establish the Reformed faith in Poland”.17

When he met Dr. Giovanni Paolo Alciati della Motta, discussions on the Trinity influenced Stancaro’s views on antitrinitarianism which caused him towards a more Unitarian viewpoint. Stancaro[vii] constantly stirred up the exegetical pot in antitrinitarian circles by repeatedly bringing up doctrinal innovations until Faustus Socinus arrived to settle the trinitarian question.

Pre-Socinian Polish Brethren

In short, the views of the Italian antitrinitarians were a stage on the way to Socinianism. Of all the Italians, Giovanni Valentino Gentile and Dr. Giovanni Paolo Alciati della Motta caused thinking in Polish antitrinitarian circles to shift further away from their own indigenous antitrinitarianism and towards a position that was Proto-Servetian. They were ready to accept the structure Faustus Socinius would provide to their seemingly chaotic and ever-shifting views.

In the next article, I introduce Faustus Socinius who as the leading theologian of the Polish Brethren brought the teachings of the Polish Brethren a wider audience, especially in England and eventually the new English colonies of America.

Socinian was the name given to the Christian movement called the Polish Brethren but they themselves didn’t use that term. It was not applied to the movement until the seventeenth century in England. They called themselves the Polish Brethren or just simply Brethren.

Earl Morse Wilbur. A HISTORY OF UNITARIANISM Volume I (1945) A History of Unitarianism Socinianism and its Antecedents. (United States: Beacon Press, 1945, 1972), 283. She was not explicitly an antitrinitarian nor was she charged with that offense. Finding the Beginning of such a movement as Socinianism is fraught with difficulties as is evidenced by the rival “beginnings” posited. This paper follows Wilbur’s judgment for lack of an evidence to the contrary.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 284.

See Gonesius, Peter. In Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

Wilbur, Unitarianism. 79. Wilbur writes, “It was among these northern Italian Anabaptists that a definite formulation of Unitarian doctrine was first adopted for purposes of propaganda; and this is apparently to be traced to the two books on the Trinity which Servetus had published in 1531-31.”

The antitrinitarians in the 16th century did not share a common formula of non-Trinity views. For example, Servetus’ views differed significantly from that of the Polish Brethren (Socinians). This might be explained by the different social, political and intellectual backgrounds between them.

Wilbur, Unitarianism. 79. Wilbur writes, “It was among these northern Italian Anabaptists that a definite formulation of Unitarian doctrine was first adopted for purposes of propaganda; and this is apparently to be traced to the two books on the Trinity which Servetus had published in 1531-31.”

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 213.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 89.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 96. He had criticized ecclesiastical tyranny.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 216.

Gribaldi’s views are: “Father, Son and Holy Spirit are really three distinct beings, each of them very God. The Father is self-existent, a sort of supreme being like Jove, chief of the Gods; while the Son and the Holy Spirit are derived from him, and subordinate. Taken concretely, the persons are distinct; taken abstractly, they are one and the same divinity, as manifestations of one power and wisdom. Thus taken, the mind easily understands their unity; but the usual notion of a triune God is an incomprehensible scholastic dream.” Wilbur, Unitarians, 222.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 216.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 223.

Gentile’s view on the Trinity was influenced by Gribaldi. “Aside from the usual objections to the doctrine of the Trinity, it is want of clear support from Scripture, and the unscriptural terms used to explain it, and the further objection (derived from Servetus) to the communicatio idiomatiom as an explanation of the union of the two natures in Christ, he held that only the father is self-existent, while the Son and the Holy Spirit are derived from him and subordinate. In the Godhead he asserted the existence of three distinct eternal spirits, equally divine, yet differing in rank, dignity and character; while (again like Servetus) he condemned Calvin’s view of the Trinity as one that led to a Quaternity.”

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 236. Wilbur states this view is Tritheism, a middle ground between the Sabellianism of Servetus and the Arianism of the Polish Brethren although it is questionable whether Servetus was a Sabellianist and the Polish Brethren were Arian.

Wilbur, Unitarianism, 315.