Updated: January 20, 2024

In April 1534, two French sailing ships sighted breakers hitting cold and forbidden looking cliffs of the New World. They had sailed from France following a well-known sailing route west across the north Atlantic and after 33 brutal days of treacherous seas, rotten food and the usual sea sicknesses reached the most easterly coasts of the new world. Jacques Cartier arrived at the easternmost point of an island called by the English New Founde Land but the French called it Terra Nova.

The French fishermen were well aware of the rich fishing resources of Terra Nova. Fishermen from the Basque country, Brittany and Bristol kept the old world supplied with abundant fish, whale meat and whale oil for their Friday meat fasts. These fishermen had no interest in creating settlements nor were they interested in spreading awareness of where exactly they were catching all this fish. They worked hard to keep the location of Terra Nova a trade secret. So, they were not happy when English and French explorers decided to take the same route across the North Atlantic on missions to find a route to China and at the same time grab their own slice of the new world before their rivals claimed it all. By the early 1500s, the Spanish and Portuguese had already claimed vast lands in the southern part of what was soon to be called America. In the north, the English jumped at the opportunity under the Viennese John Cabot. Now it was the time for the French to claim land for themselves. And leading this effort was an experienced sailor named Jacques Cartier.

The Secret Fishing Grounds of Terra Nova

The first to see Terra Nova or New Founde Land were the Norse in 982 or 983 CE who after island-hopping their way across the freezing waters of the North Atlantic reached the coasts of North America. Previously they had encountered a green land they called Iceland and then an icy land they called Greenland. After making settlements in Iceland, a few Norse sailors continued west past Greenland and after a considerable journey spotted land they had never seen before. This was the rocky coast of what we call today Labrador. Following south along this coastline they eventually arrived at what seemed to be a very wide river (today’s Straight of Belle Isle) then made landfall on the north-eastern coast of what would become Newfoundland at a place called today Cape Norman. Although this land was rocky and of poor soil, they nevertheless called it Vineland1. Eventually they built a settlement. It is possible they continued their journey southward reaching as far as present-day Nova Scotia or even further south.

But they did not stay. The indigenous peoples, probably the Beothuk2, were unwelcoming or more likely the land was unforgiving to the Norse voyagers.

Another five hundred years would elapse before any Europeans would venture across the northern latitudes to reach Vineland. However, during the late 15th century, English fishermen working out of Bristol, England found this new land just in time to christen it with the name New Founde Land. What they found was the rich fishing grounds on a shelf of the Atlantic called the Grand Banks. Fishermen scooped up vast catches of cod and hunted whales for their meat and to boil the rest to create whale oil.

What the native populations thought about all this activity is not recorded. What is certain about these interactions was indigenous peoples, perhaps the Mi’kmaq or Innu (Montagnais) but most likely the Beothuk peoples, kept their distance while these pale people with their odd boats did their work on the beaches.

The Grand Banks had that name for good reason. The schools of cod were so thick that it was said “a fisherman could step out of the boat and walk across the backs of the cod swimming in the sea.” This is mostly likely an exaggeration, but the Bristol merchants found fishing for cod extremely profitable to finance fishing expeditions across dangerous waters to bring home barrels full of preserved cod.3

However, the English were not the only fishing fleets pulling in cod. Basque fishermen from the Iberian Peninsula soon made their way to these waters around 1525. Both the English and the Basque did their level best to keep these waters a secret to anyone else who might try to cut into their business. Despite their best efforts, this would not last.

John Cabot

In 1496 a Genoese explorer named Giovanni Caboto arrived in England after a futile effort to convince the Spanish and Portuguese kings to back his adventure to find a northern route to China. Caboto convinced King Henry VII, who reigned from 1485 to 1509, that Christopher Columbus’ discovery of a western route to China could be achieved by taking a northern route. He convinced the king tha it would be a faster route than a southern crossing. For his daring, the English gave him with an English name John Cabot.

Cabot’s first attempt in 1496 failed after less than a week at sea due to horrendous weather. He made another attempt the next year which succeeded beyond expectations. After a 35-day sailing across the Northern Atlantic, Cabot made landfall on 24th of June 1497 at an island later to be called New Founde Land. He and his crew took a small boat and landed on a rocky beach to search for any inhabitants. He walked up the beach to a forest to find only evidence that someone had recently put out a fire and fled into the woods.

When the indigenous people (probably the Beothuk) saw Cabot’s ships out in the ocean, years of experience told them to flee into the forests. Having failed to see any inhabitants, Cabot and his crew returned to their ship. When the Beothuk people waited long enough to ensure these strange people were not returning, they made their way back to their ocean-side camps. Meanwhile the English explorer, according to accounts of the voyage, continued sailing north-west for 30 days following the coastline north. After reaching the northernmost point of the coastline, Cabot sailed east returning below Iceland and Ireland to land in Brittany only to make his way back to his home port of Bristol. And so was the first “official” English contact with the new world. Cabot claimed the land for the English king and raised the Papal banner declaring the land a Roman Catholic country.

Cabot’s real discovery though was to “break a trade secret” held by the European fishermen who regularly plied these waters for its lucrative cod and whale catches.

John Cabot made a third journey across the Atlantic in 1498 but this was to be his last. The records are sketchy but at some point, he was supposedly "lost at sea never to be heard of again." However, it is equally possible that he and his five ships returned but the arrival was not recorded, or the record lost to history.

His legacy which was to claim New Founde Land for the English crown. More significantly, his voyage led to a dawning realization in Europe that this new land was not China but an entirely new continent. The early explorers' such as Cabot contribution to European knowledge was an “intellectual discovery of America” which means what these explorers saw was not China but an entirely new world. From then on, the English dropped the notion that these lands were somehow connected to China.4

Other English sailors pushed the boundaries of discovery including John Cabot’s son Sebastien Cabot who may have entered Hudson’s Bay. However, instead of understanding the true value of what they had discovered, the Europeans thought this new world was merely an obstacle to the great riches of China. They saw this new land as having little promise for great riches and the peoples who inhabited it had “little to commend themselves.” Finding a route to China through this massive obstacle became the obsession of every subsequent exploration of the new world. Their overriding question was “How can we get around it to get to China!”

Race to find a route to China

As for the peoples who inhabited New Founde Land, they were well aware of the activities of these strange people and their strange ships. They seemed to have tolerated the English and Basque fishermen coming ashore to dry and prepare their fish catches for the return journeys. If these strange people left them alone and left at the end of the warm weather, all was good. And it seems these European fishermen were glad not to interfere with these inhabitants, mostly because the Beothuk did not want any contact with the Europeans. Other peoples such as the Mi’kmaq or Innu (Montagnais) did make contact with Europeans but in other areas around the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The obsession to find a route to China turned into a race to claim territory. Taking possessions of things has a long pedigree amongst the powerful - the greater the power, the greater and larger the possessions need to be. Vanity, self absorption, and narcissism drove the great and powerful to take land-grabbing to an absurd level during the so-called Age of Discovery.

Furthermore, technological innovations such as the sextant allowed sailors to track their voyages across open oceans. Improvements in sailing ship design, sailing skills and learning the use of trade winds allowed for unheard of sea voyages into places unknown and hitherto unknowable.

For coastal European nations such as Spain, Portugal, France and England, the discovery in the 15th century of a new world sent shock waves throughout Europe, including a vast influx of gold and silver to European economies. Christopher Columbus’ discovery of a new world in 1492 as well Amerigo Vespucci’s accounts of even more territory in the next decade led to a rush to claim parts of this new land mass for European monarchs. With the help of experienced sailors from Venice, Genoa and other Italian city-states, the great sea powers of Spain and Portugal financed voyages across the sea. France wanted part of the new lands, and if they could find a shorter route to China at the same time, all the better.

Jamus Verrazzano, the forgotten explorer

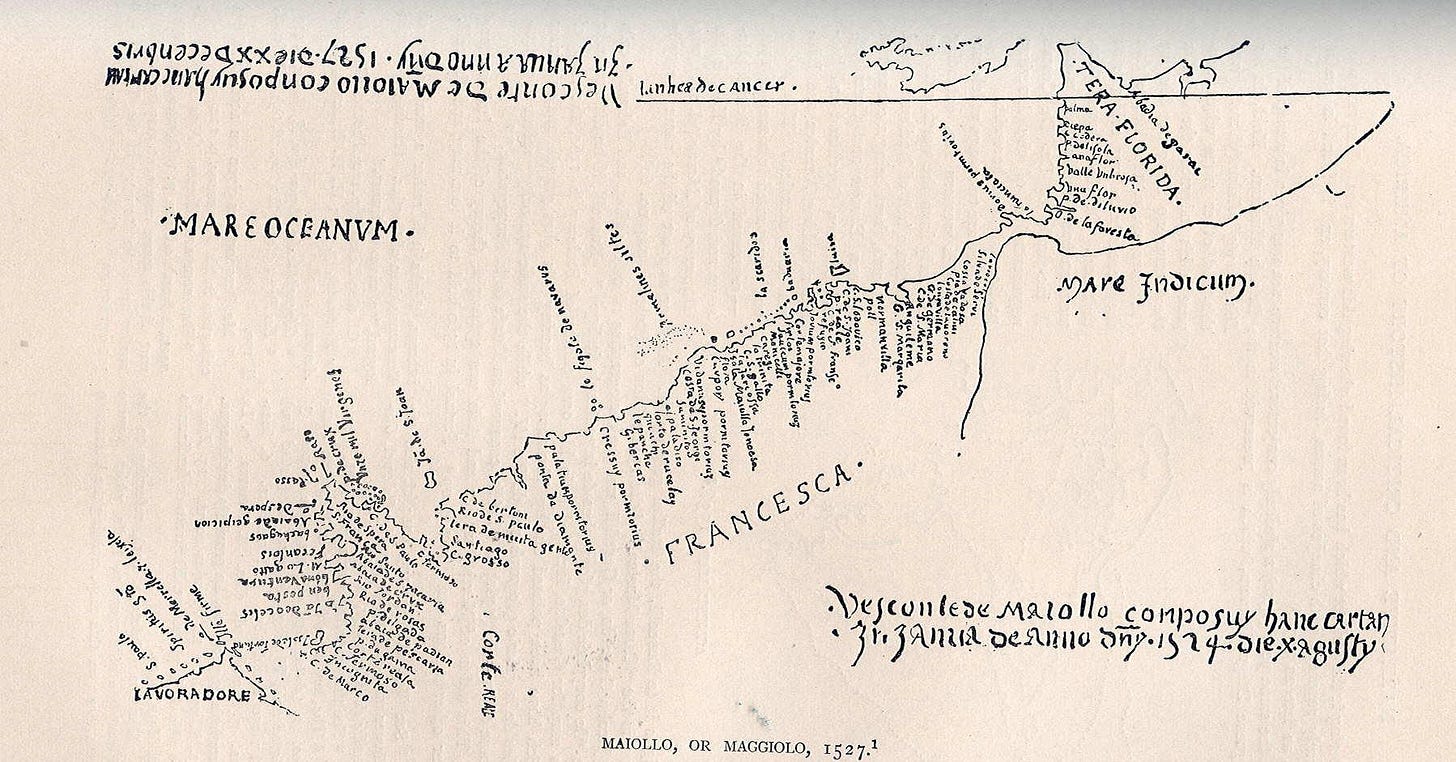

The route to Newfoundland - as it came to be known - was well known by the mid 1500’s. In 1524 the Italian Janus Verrazanus, also known as Verrazzano, took up the challenge under the patronage of the Francis I, King of France. Verranzzano and his crew sailed across the Atlantic taking a southerly route and made landfall somewhere near present-day North Carolina. Heading north along the coast, he reached the waters near present day New York and then stayed for a few weeks within Narraganset Bay near present day Rhode Island. There he rested, took on more his supplies such as fresh water, food and wood, and make any necessary repairs to his ship. He also met inhabitants of the area including the Wampanoag and the Narraganset.

Heading north along the coast he ventured too far east and entirely missed the coastline of what was to be Nova Scotia but managed to land on an island known later as Cape Breton Island. Meeting inhabitants of this island, the Mik’maq, he promptly captured a native boy to prove his success. This appalling action on the part of Verrazzano can only have increased the mistrust the inhabitants had for these people of the sea. To lose a child is traumatic but for a people whose identity was bound up in generations of ancestors and generations of descendants, losing one child could break that bond which would be an unbearable loss.

With the abducted child, Verrazzano took his voyage north reaching New Founde Land and then sailed east across to France. Today he is most widely known as the name of a bridge near New York City. He also began the practice of naming places in the new world after persons and places in the Old World5.

By the early 1500s, southern and northern routes to North America were beginning to be mapped and became well known to the leading European coastal nations.

Jacques Cartier’s first voyage - April 20, 1534

The next French explorer would be far more successful than Verrazzano.

Jacques Cartier was born in St. Malo in Brittany. "A fearless and experienced mariner", he may have already visited New Founde Land as part of fishing crews and even have sailed to Brazil on various expeditions. He knew the open ocean. He felt completely in his element on any sea going vessel in his time. He understood the winds, waves and clouds and knew how to navigate the sea using dead-reckoning, compasses, celestial navigation, and other tools like the Quadrant.

With this experience as evidence of his skills, Cartier sought a commission from the King of France, Francis I, to sail to North America to first, claim territory for France and second, find a northern route to China6. Having obtained a royal commission to claim territory for his most Christian Majesty, Cartier set about preparing his expedition. Unlike French fishermen, Cartier was not interested in trade but in exploration and for this effort he was granted two 60-ton ships each with a crew of 61 experienced sailors, a handful of nobles, medical personnel and others who Cartier thought valuable for the journey.

Sailing from France on 20 April 1534, Cartier took the north Atlantic route to reach the north-eastern coast of New Found Land in a record 20 days. After anchoring off the coast for 10 days to repair his boats, he set sail north along the rugged coastline. After several days, his ships anchored off the inhospitable Funk Island7 to fill his barrels with hundreds of easily captured Great Auks and other birds. They also captured a stray Polar Bear they found swimming towards the coastline from Funk Island. Continuing north the ships reached a channel that emerged from the west, later called the Straight of Belle Isle which the Norse had also crossed half a millennium previously. Still unaware this coastline was part of a large island, Cartier led his two ships into the channel and to find a safe harbor.8 Passing to the south of Belle Isle9 they then sailed into an inlet with Cap Norman on his left and Red Bay on his right.

Returning to the channel to head west, the waters began to narrow. After a few days sailing, the channel opened up into a great inner sea. One wonders what he must have thought after seeing this great expanse of water as he would not have expected to see open water. Despite this uncertainty, he sailed on to continue his westward voyage to find an inland route to China.

He then turned his ships south-west to follow the eastern coastline. At every sighting of land, he found only rocky shorelines. At one point he observed that this land “must have been the land God gave to Cain” due to its barrenness.

Leaving the coastline, he headed west only to discover a set of islands that he found were full of grasslands and trees. These were the Magdalene Islands in the middle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Cartier had just missed the opening to the Atlantic and would not know it until his second voyage.

He then pushed on westward and spotted another large island, now called Prince Edward Island. Cartier recorded the finding as a very “pleasant and fertile land” unaware that it too was an island. Turning his ships on a northwesterly route, he reached another large coastline. Following this coast northward, he discovered an entrance to a river, today called the Miramichi River, but did not enter it. Continuing on further north he encountered another inlet which was very wide and deep. He suspected this was merely the entrance to a great river that crossed the continent. As he sailed deep into the inlet the weather turned extremely hot and humid. He called it Chaleur Bay (the Bay of Heat or as we might say, the Bay of Unbearable Humidity) because the weather in this bay was unbearably hot for the sailors. He briefly encountered about 200 local inhabitants in small boats hunting for seals. No record exists of any extensive meeting except to conduct trade. These people were most likely the Mi’kmaq. Cartier wrote (translated and 16th century English spelling retained):

There we stayed from the fourth of July until the twelfth: while we were there, on Munday being the sixth of the moneth, Service being done, wee with one of our boates went to discover a Cape and point of land that on the Westerne side was about seven or eight leagues from us, to see which way it did bend, and being within halfe a league of it, wee sawe two companies of boates of wilde men going from one land to the other: their boates were in number about fourtie or fiftie. One part of the which came to the said point, and a great number of men went on shore making a great noise, beckening unto us that wee should come on land, shewing us certaine skinnes upon pieces of wood, but because we had but one onely boat, wee would not goe to them, but went to the other side lying in the See: they seeing us flee, prepared two of their boats to follow us, with which came also five more of them that were comming from the Sea side, all which approched neere unto our boate, dancing, and making many signes of joy and mirth, as it were desiring our friendship, saying in their tongue Napeu tondamen assurtah, with many other words that we understood not. But because (as we have said) we had but one boat, wee would not stand to their courtesie, but made signes unto them that they should turne back, which they would not do, but with great furie came toward us: and suddenly with their boates compassed us about: and be cause they would not away from us by any signes that we could make, we shot off two pieces among them, which did 80 terrifie them, that they put themselves to flight toward the sayde point, making a great noise: and having staid a while, they began anew, even as at the first to come to us againe, and being come neere our boat wee strucke at them with two lances, which thing was so great a terrour unto them, that with great haste they beganne to flee, and would no more follow us.10

Cartier had no idea what language they were speaking. Later, two of Cartier’s men volunteered to go to shore to meet with them and trade ironware, some knives, and a red hat in exchange for some skins the peoples had with them. Cartier then proceeded deeper into the bay in small boats and realized these waters ended in a cove. Disappointed, he turned back towards his ships.

Cartier explores the Gulf of St. Lawrence

Cartier then turned the ships around and sailed back to the open waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, probably to the relief of his crews, and then turned north to follow the coastline. He reached another inlet. This was the entrance of what would be known as the Baie de Gaspé or Gaspé Bay. Encountering days of stormy weather and unable to make any progress, the two ships entered the bay searching for a safe harbour. He spotted a channel leading to a camp site of the local inhabitants. Entering the channel, he encountered a group of over three hundred men, women and children who were fishing for Mackerel. Cartier then sent two men to offer them items for trade. In exchange for the iron and tin items, the people gave them seal skins and whatever else the local peoples could offer. Apparently, these indigenous peoples were familiar with sailors entering their waters and offering items for trade.

Sailing deeper into the bay, they entered another harbor and encountered a huge crowd of indigenous peoples Cartier would learn are called Iroquois. About forty boats approached the ships. Cartier’s men offered them all sorts of items of small value but appreciated by the local people. Cartier’s observation of these people is worth repeating here.

Neither in nature nor in language, doe they any whit agree with them which we found first : their heads be altogether shaven, except one bush of haire which they suffer to grow upon the top of their crowne as long as a horse taile, and then with certaine leather strings binde it in a knot upon their heads. They have no other dwelling but their boates, which they turne upside downe, and under them they lay themselves all along upon the bare ground. They eate their flesh almost raw, save onely that they heat it a little upon timbers of coales, so doe they their fish.11

Cartier spent several days with these people observing their ways and customs, Cartier concluding these people were a trifle and “wilde”. He then did his duty as a representative of the French king Francis I and planted a cross as a symbol of French territory.

Upon the 25 of the moneth, wee caused a faire high Crosse to be made of the height of thirty foote, which was made in the presence of many of them, upon the point of the entrance of the sayd haven, in the middest whereof we hanged up a Shield with three Floure de Luces in it, and in the top was carved in the wood with Anticke letters this posie, Vive le Roy de France. Then before them all we set it upon the sayd point.

Raising a totem, as they saw it, in the territory of the Iroquois was a direct challenge to their sense of ownership of the land. Donnacona, their “Captain” and the rest of the Iroquois changed their mood and became clearly hostile. Approaching Cartier’s ship wearing a symbol of authority (a bear’s skin) he demonstrated his extreme displeasure with the cross and that they should not have erected it without his approval. Cartier then engaged in trickery and deception by claiming the cross was a signpost to help him locate the landmark on later voyages.

Cartier abducts Taignoagny and Domagaya

Donnacona protested but this time Cartier and his men responded by abducting two men. Sailors reached out and grabbed Donnacona’s boat, then jumped in and forced two young men Taignoagny and Domagaya (some argue they were Donnacona’s sons) to enter the French boats. Cartier played the noble character and offered to introduce these two men to Cartier’s homeland France and to bring them back on his next voyage bearing gifts from France. At least that part was true. In so doing, this would end up becoming the first cultural exchange between the native people from North America and Europe.

The trickery involved in getting them on board the ship is disturbing enough but not out of the ordinary for the times. Assuaged at this promise that his “sons” would return, Donnacona reluctantly agreed. Looking at it from his perspective, what other choice did he have? Despite the promises, the power in this transaction did not rest with Donnacona but with Cartier and his weapons of war, possibly the arquebus.

Cartier left the harbor and sailed east sailing around an island he called Isle de l'Assomption, today called Anticosti Island, having completely failed to discover the entrance to the St. Lawrence River despite it being less than a day’s sailing away. Turning east he followed the coastline of l'Assomption and noted that the land was completely devoid of trees but full of meadows. After reaching the southern tip of the island, the ships sailed north with the island to the south and a very rocky and mountainous land to the north (present day Quebec). As the winds were unfavorable, they decided to head east to the Straight of Belle Isle hoping to make it back to France without danger.

Cartier records an odd incident at this point. Somewhere along the northern coast he encountered French or Basque fishermen. They approached the ships to tell Cartier that they were heading to area where Cartier had just departed near the Isle de l'Assomption. However, they called the waters from where Cartier had just circumnavigated “Big Bay” suggesting they were unaware, as Cartier was now aware, that this bay was actually an exceptionally large inland sea, or in other words, a gulf.

Cartier returns to France August 15, 1534

On the 5th of August they reached a point on the northern coast of New Founde Land when they encountered a powerful storm. Finding no suitable harbor in which to anchor, they endured the storm from the 5th to the 8th of August. The winds pushed them toward the north shore where they ended up on the 8th. On the 9th of August the sailed along the coast and approached a place Cartier called Blanc Sablon. It being Sunday, they held their worship service there. As the next day, the 10th of August 1534, was the feast day of St. Laurent, Cartier memorialized this day by calling the bay, St. Lawrence Bay and the open waters they just exited as Golfe du Saint-Laurent, or the Gulf of St. Lawrence.12

On the 15th of August they departed Blanc Sablon and

after saying Mass, and with good weather we came as far as to mid-ocean between New Land and Brittany, at which place we had to remain three continuous days with a furious tempest of head winds, the which, with the help of God, we suffered and endured; and after that we had weather at will, so that we arrived at the harbor of St. Malo, from which we had departed, the fifth day of September in the said year [1535].13

Results of Cartier’s first voyage

What did Cartier accomplish? Despite his roguish reputation for abducting the two Iroquois men, Cartier provided invaluable information about the first encounters with Indigenous peoples of Canada. He provided the first detailed description of the habits and culture of these peoples. Despite his subterfuge, he would come to develop a lasting relationship with Donnacona and his people. And he managed to claim land for the French king. He also gave detailed descriptions of islands, waters, bays, points of land and was the first to name these locations, some of which are still in use today.

The St. Lawrence Iroquois, as these peoples would come to be called, established their first long term relationships with a European. And despite the obvious imbalance of power, Donnacona, their leader, demonstrated integrity, honesty, and dignity. His people showed themselves to be friendly, curious, generous, and creative with what was available to them. They were resourceful and knew the sea and knew where fish and seals could be harvested and how to store them for the winter season. They also knew what plants could be eaten and where to find them. All this would become vital knowledge for the first settlers in France’s new territory.

From Cartier’s perspective, however, these people were “wilde” but so was nature. The St. Lawrence Iroquois learned to live from what nature provided with minimal tools. They built sea-worthy boats made from tree bark, twine and bent branches and even used them as portable homes during the night under which they could be protected from the elements.

The Iroquois were glad to get items they had no means of making, such as beads, tin bells, iron pots and bowls and knives. And they did not take long to find the best use of them.

As for Cartier and Taignoagny and Domagaya, they would become a sensation in France and lead to more adventures across the sea. They would return with Cartier on his second voyage, which we will take up in the next article.

The Norse may have had access by trade or by discovery of the wild grapes on New Brunswick and the St. Lawrence river valley in Quebec.

Beothuk. See The Canadian Encyclopedia.

This trade eventually became part of trade between the West Indies, Newfoundland and England, all of which involved slavery.

See the entry for CABOT (Caboto), JOHN (Giovanni) in The Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume 1.

See the entry for Giovanni da Verrazzano in the online Encyclopedia Britannica.

See the entry for Jacques Cartier in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Cartier may have known this island based on reports from fishermen, or perhaps from his own journeys

At one harbor his ships laid at anchor waiting out a storm but just on the other side of the point were the ruins of a Viking settlement long overgrown.

Some of these landmarks had already been named but Cartier did provide names to other landmarks and islands. Current names help to identify the territories.

Pg. 19. Burrage, H. S. (ed.). EARLY ENGLISH AND FRENCH VOYAGES· CHIEFLY FROM HAKLUYT 1684-1608. C. Scribner's Sons, 1906.

Pg. 23. Cook, R. The Voyages of Jacques Cartier. University of Toronto Press, 1993.

I have had to surmise this from all available records as I could not find any mention of when the Gulf became known as the Gulf of St. Lawrence. However, all other instances where it is so named, this event provides the most reasonable suggestion as to why it became known by its current name. It is equally possible it was the crew that first used this appellation and by common usage entered the vocabulary of the French sailors of St. Malo and ultimately named so on maps.

Pp 119-120. Baxter, J. Memoirs of Jacques Cartier. 1905. Portland, Maine.