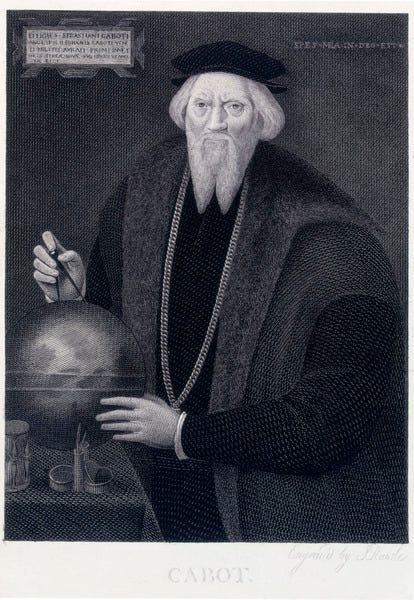

18. Sebastian Cabot - scoundrel, genius or both

Sebastian Cabot, son of John Cabot, left a legacy full of dubious achievements and incompetent leadership. Was he the Great Age of Exploration's first self-serving fraud and scoundrel?

Updated: 16.12.2024

“SEBASTIAN Cabot was a man capable of disguising the truth, whenever it was to his interest to do so.”1

Sebastian Cabot was the middle child - as was I, not like there is anything wrong about it. And like me, he crossed the Atlantic Ocean several times. But this is where the similarity ends. I spent the many crossings crammed into a metal tube at 30,000 feet above the water with my knees smashed against the seat ahead of mine. Mind you, Sebastian Cabot may not have had a better experience. He spent the crossings in fragile barques or caravels buffeted by intense waves and harrowing storms. He used this type of sailing vessel to reach Brazil and Labrador.

I knew that I would write about Sebastian Cabot after completing the stories of John Cabot’s discovery of Newfoundland. I had no idea what a challenge this would turn out to be. He is a controversial historical figure. During research, he came across as a scoundrel and a fraud. At other times he exhibited flashes of genius. Was he more of the former and less of the latter or merely both at the same time?

In 1488 John Cabot left Venice to escape debt. He left Italy with his wife, Mattea, and their sons Ludovico, Sebastian and Sancio. Sebastian must have been a teenager at this point. When the family arrived in Bristol, England some time before 1496, Sebastian must have been an adult as he was included in the Patent given by King Henry VII to explore the new world and find a northern route to Asia. Whether Sebastian was on all or some of his father’s journeys is unclear but the experience of seeing his dad organize and lead a high risk adventure taught him many lessons about navigating the Atlantic.

Sebastian wasn’t satisfied with being a passenger on his dad’s ships. He felt he could do one better and show up his dad by piloting his own adventure to the new world. Where his dad failed, Sebastian would succeed. His dad didn’t strike it rich on his three adventures. The best he achieved was a few trinkets from natives and a barrel of fish gathered from off an island of barren rock. No spices nor riches. Sebastian was going to set the record straight and achieve where he dad failed.

Finding the fabled northwest passage (1508-1509)

So in 1508, if the story can be believed, Sebastian Cabot proposed another expedition to find a northwest passage to China. But first came the little known 1504 expedition.

Two ships were involved: the Gabriel of Bristol, mastered by Philip Ketyner, and the Jesus, under Richard Savery. Hugh Eliot and his long-term business partner, Robert Thorne, and Robert's brother, William, seem to have been the principal organisers. Eliot led the expedition, with Sebastian Cabot probably serving as pilot.2

These two ships departed in either 1504 or 1505 from Bristol for Newfoundland and brought back 67 tons of dried codfish (stockfish), which was far short of a full capacity of the ships. By 1508 this entire group fell out and sued each other over debts owed.

But in the same year in late June and using the Patent from his father, Sebastian Cabot headed out again using the same ships Gabriel and Jesus. Why this voyage? King Henry VII had little interest in the codfish as he had other sources for the fish. The King wanted a trade route to compete with the Spanish and Portuguese. The Northwest passage offered a possibility and Sebastian Cabot was convinced he could find it. So, the King encouraged him.

According to the story written by Sebastian and passed on by his friend Peter Martyr of Venice, Sebastian used his influence to get the two ships manned by 300 sailors. When ready, the ships departed Bristol and heading north they crossed the North Atlantic south of Greenland (which at the time was known as Labrador) and reaching the coast of Labrador he sailed north until a great field of icebergs hindered further progress.

In the early 16th Century, Greenland and Labrador were seen as a single landmass. Newfoundland was also seen as part of the continent of Labrador until Jacques Cartier discovered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. So, when Sebastian reached the iceberg field he thought he was sailing up an inlet, albeit a very large and wide inlet which he believed ended in a river crossing over towards China. He might have made it to Hudson’s Bay but that is uncertain.

Upon reaching the wall of icebergs, Sebastian (with his crew’s insistence) decided to turn back. Sailing south along the coast of Labrador he reached the Straight of Belle Isle thinking it was another inlet. Sailing along Newfoundland, he rounded the southern tip of the island at the dangerous Cape Race point. He then continued southwest towards Nova Scotia. Oddly he didn’t leave any place names as was the habit of the Portuguese, Basque and Spanish sailors.

At some point they wintered over somewhere along the east coast, possibly where Long Island is today or near the Hudson’s River. Whether they encountered the native populations along the way is unknown. This would have been significant and worth noting, but the record is silent.

By the Spring of 1509 they reached as far south as Chesapeake Bay where they made the decision to return to Bristol. The usual cause for explorers cutting short their trips was diminishing supplies and Sebastian’s ships may have been running short. How many sailors died of scurvy is unknown. Whatever the cause, he turned their ships north east to follow the Gulf Stream across to England.

We don’t know very much about the entire journey. Sebastian Cabot may have indulged in significant editing of his story as it didn’t achieve anything useful for his sponsor King Henry VII. If this journey actually happened, it would be a a major achievement. He and his sailors endured serious hardships on this trip. He travelled the furthest north for any English ship of the time. Yet, we know so little about it.

Where is the evidence for this trip?

During the 19th century, historians went on an unholy debate questioning each other’s interpretation of the scant records of the Cabot voyages. Each side found fault with the other’s reasoning and for perpetuating errors. The fact is, we don’t have clear records of these voyages. Most of the information is based on secondary sources and inference.

Not long after John Cabot made his three voyages (1496, 1497 and 1498) the Venetian was almost entirely forgotten. In time Sebastian came to be seen as the great explorer while his father served merely as a figurehead of the expeditions. However, by the end of the 19th century Sebastian Cabot was seen as a usurper taking his father’s achievements for his own. Perhaps that is being unfair to Sebastian’s achievements, mediocre as they were. His reputation suffered immensely nonetheless.

For over three hundred years, John Cabot’s achievements were conflated with his son Sebastian’s life, so much so that the son was considered the discoverer of New Found Land while his father was almost entirely forgotten. In time, John Cabot was believed to have gone down with his ships in 1498 and never returned to Bristol. Yet somehow Sebastian did and lived to tell the tale. How is it that the father drowned yet the son did not? It is hard to cross the t’s and dot the i’s.

Sebastian the self-promoter

Sebastian may have been the first explorer who had more of an interest in self-promotion than nation-promotion. If a story served his ego, he ran with it. Nothing would get in the way of a good lie if it meant more money, fame or promotion.

But history has a way of getting to the facts.

The American historian and lawyer Henry Harrisse wrote in 1896 a detailed account of the life of John and Sebastian Cabot called John Cabot, the Discoverer of North American and Sebastian his Son. Harrisse’s legal mind comes across on almost every page of his book. Using a lawyer’s line of questioning, John and Sebastian take their turn sitting in the dock while Harrisse challenges their assertions and forces them to prove what they have claimed.

No stone is unturned. In the end, John Cabot gets exonerated while Sebastian Cabot is given his due as a mediocre navigator, dubious mapmaker and who isn’t afraid of plagiarism. To be fair, plagiarism in mapmaking was par for the course in an age where knowledge of the New World was a closely guarded secret and sharing this knowledge could lead to prison. Taking knowledge gained elsewhere and claiming it as one’s own could prevent exile or worse - years rotting in prison. So, it was in Sebastian’s own interest to claim knowledge of Newfoundland as his own even though that knowledge was the property of the King of England.

The Bristol historians Jones and Condon summarized Sebastian Cabot’s 1508 voyage:

As a navigator and promoter of exploration voyages, Sebastian's main interest was to talk-up his personal achievements as a way of bolstering his own reputation. So his voyage accounts cannot be taken at face value. Nevertheless, they should not be written off entirely. In particular, some credence should be given of his story of a voyage apparently undertaken in 1508-9, particularly given the earliest description of it was penned just a few years after it took place, when there were still many other people around who could have gainsaid him. That Sebastian was absent from England in 1508 is almost certain, since he did not collect the first installment of his pension for that year until May 1509.

They don’t question Sebastian took the voyage but how much of the story is true is an open question. This might be the reason for lack of place naming, death of sailors, meeting native peoples and other evidence of a long voyage. Did he make it to the far north then just turn south until he found a spot to winter over? It’s possible. For Sebastian finding a northern route to China became an impossible dream and he dismissed the real riches - the cod off the coast of Newfoundland.

Sebastian Cabot as Spanish Pilot Major

Around 1512 we find Sebastian Cabot in Spain. He was offered a position in Spain under King Ferdinand of Aragon. The King wanted to know more about the fisheries off the Baccalos (Newfoundland). Sebastian moved there in 1512 after young King Henry VIII permitted him to depart for Aragon. The King wanted to enhance the relations between the two Kingdoms and Sebastian was part of that effort.

Cabot was appointed a naval captain and given a salary of 50,000 maravedí (Spanish currency of the time). Once in Spain Sebastian was given another 10,000 for his services. Cabot was then appointed Captian de Mar and afterwards appointed Pilot.(Captain was a leader of an expedition, not a naval officer. Navigator was the role of Pilots.) Cabot arrived in Spain but the King died before Sebastian could take up the position.

In 1516 he departed Aragon for England due to the death of Ferdinand and the delay of the arrival of the heir Charles V. In the following year he returned to Spain. Why he went to England is uncertain, but possibly to arrange of voyage to the New world, which never came to be.

Back in Spain he was appointed Pilot-Major by Charles V, a very significant role as he was to head of all Spanish expeditions on behalf of Charles V. He asked for and received an annual income of 25,000 maravedí for life.

For Sebastian, this was an incredible turn of events. At this point, he knew his worth in international politics and used his experience on his North Atlantic voyages to spin out a high-profile position in Spain. It is probably during this period that his father was slowly removed as the discoverer of Newfoundland.

Expedition to the Spice Islands (Moluccas)

In 1524 Sebastian Cabot was chosen to lead an expedition to the region of the Moluccas. Cabot convinced Charles V that he knew a shorter route there but what this route was is not recorded.

The Moluccas, a part of present day Indonesia, were known in the 16th Century as the Spice Islands whose main appeal to Europeans was as a source of extremely valuable nutmeg and cloves. It had as much value in Cabot’s day as Rare Earth minerals have today to EV battery manufacturers.

ALLURED by the specimens of cloves, nutmegs and cinnamon which EI Cano had brought from the Indian Seas in 1522 and encouraged by the representations of Sebastian Cabot that there were other spice islands in the region of the Moluccas which could be reached by a shorter route than Magellan's and which he even pretended to have already visited, a number of Sevillian merchants formed a company for a voyage in quest of these productive isles.3

Sebastian Cabot was authorized by Charles V to lead a fleet of four ships with at least 200 sailors and other professions to sail to the Moluccas using Cabot’s supposed “shorter route”. However, Charles V may have authorized the journey for a secondary purpose which was to map the western coast of South America. It was not entirely clear what lay in the western edge of “Brazil” and as the Spanish explorer Garcia de Loaysa was already tasked to journey to the Spice Islands, the King may have thought Cabot’s trip might serve this additional purpose.

Sailing from the same departure port as Columbus and Magellen, Cabot left San Lucar de Barremeda on April 3rd, 1526 and headed for the Canary Islands. After a short sailing, they anchored at the port of Palma in the Canary Islands. Then on April 27th they departed the Canary Islands for the Cape Verde Islands sailing near the coast of Africa. There is no evidence he landed at Cape Verde but he made the first of many lapses of judgement when he sailed directly into the middle of the South Atlantic and faced contrary winds taking him far off course. Rather than heading south to the tip of South America he was driven east towards the coast of Brazil. Aside from going in the wrong direction, this mistake resulted in his crew suffering from thirst.

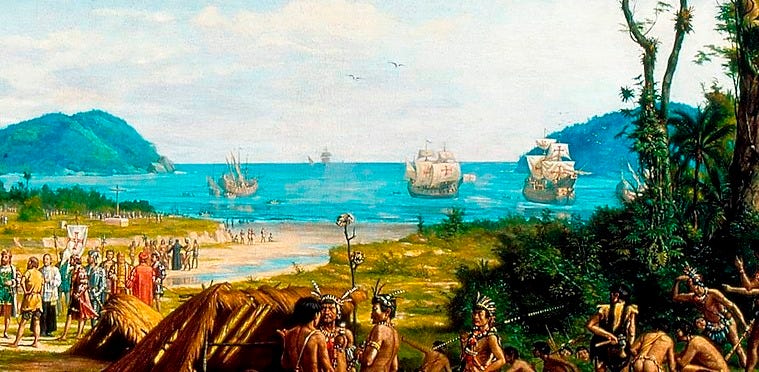

On the 3rd of June they spotted land. They had reached north of Pernambuco (now Recife, Brazil) situated on the eastern bulge of Brazil. Having sent a ship with empty casks to have them filled with water, the crew in the ship spotted a fort. Upon arriving at the fort they found it under command of Portuguese fishermen. The Spaniards were treated well by the Portuguese who provided for their needs.

It was at this fort that Sebastian Cabot made his second fateful decision. While at Permambuco, Cabot was told about vast mineral wealth of the La Plata region (between Urugray and Argentina). Asking where he might find more information about this region, Cabot was told there were survivors of Spanish expeditions to this region scattered amongst Portuguese settlements along the coast of Brazil. Ignoring his mission to the Moluccas, Cabot determined to sail south to find some of these people to get more information about La Plata.4

After waiting three months at Permambuco for favourable winds, the Spanish ships departed south following the coast of Brazil stopping in Salvador (present day Rio de Janeiro) and Sao Vicente.5 The last location had a fort built by the Portuguese and become the first permanent Portuguese settlement in Brazil. A number of sick and weary crew decided to stay with the Portuguese in their fort.

Arriving at the Rio de Solis - known today as the Rio del la Plata estuary - on or about March 26th 1527, Cabot sailed up towards the top of the estuary.

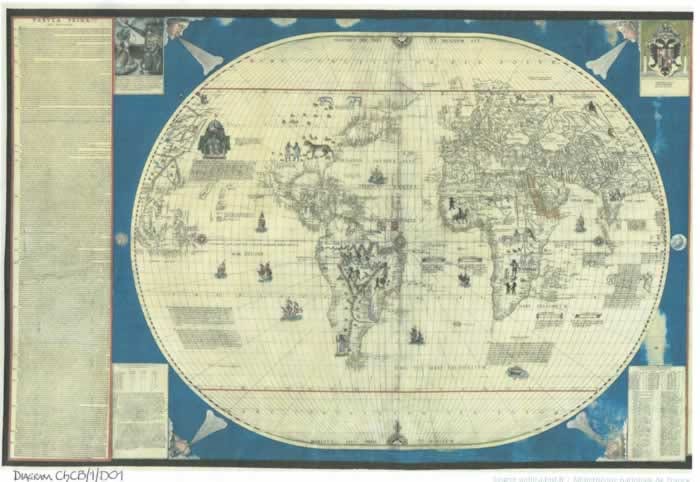

Cabot’s description of the estuary and rivers is not particularly accurate, as can be seen in this portion of his 1553 planisphere. The rivers are wider and shorter than they are in reality, so finding where he travelled on a modern map takes some interpretation.

On the 7th of April they arrived at the wide opening of the Rio de Sancta Barbara - today known as the Uruguay River - which was and still is dotted with many islands and sandbars. On one of the islands Cabot ordered a storehouse to be constructed to offload supplies and baggage. This lightened the ships and allowed them to navigate the shallow inland rivers. After ascending the river for some time they reached the mouth of the Rio de San Salvador, still named so today, and spent a few weeks there.

The native peoples must have spotted them wandering around the area and felt threatened. They attacked those on land and killed two sailors. Cabot then decided to build a fort naming it Sancti Spiritu. It has today grown into a small town and is known as one of the settlements founded by Cabot.

By the 14th of August Cabot and his crews were ensconced inside it. Fearing for the twelve soldiers guarding their supplies in their first fort, a ship was sent to retrieve them and the supplies and bring them to the fort. By August 28 they returned and the entire crew and supplies were brought inside Sanct Spiritu.

On December 23rd, 1527 Cabot left two of his largest ships and crews at Sancti Spiritu to begin his exploration of the La Plata region. On board was a Spaniard he found abandoned on an island in the Rio de Solis by a previous explorer and who had learned the language of the native peoples. He took the two smaller ships along the Rio Paraná to make their way inland in search of the fabled region of great wealth.6

After sailing some days along the Rio Paraná, he entered the Paraquay river. At this point Cabot became the first European to venture that far into the interior of South America. However, while on the Paraguay, Cabot sent one of the ships ahead in search of food. While on this journey, they spotted natives who seemed to encourage them to come ashore by friendly dances and songs. When they reached the shoreline, instead of a friendly greeting, the natives jumped into the boats and attacked them. In the struggle eighteen sailors were killed. The survivors fled back to inform Cabot about the attack. Cabot then authorized the slaughter of as many natives as they could find.

After this debacle, Cabot continued some distance upstream. But finally facing discontent from the crew and feeling they were no nearer the objective, he decided to return to Sanct Spiritu having failed to locate this great source of wealth.

Many other events occurred which space prevents from relating but it appears Sebastian Cabot had enough of exploring. One event is worth mentioning. A vast army of natives came and attacked the fort at Sancti Spiritu where some of Cabot’s crew died. After fending off another native attack they suffered severe hunger and more died by starvation.

Taking stock of his supplies and precarious state in the fort, he made the decision to depart for Spain.

Leaving the Rio La Plata estuary sometime in November 1529, he took four months to make a leisurely journey north along the Brazilian coast. After reaching the northern most point of Brazil, he then crossed the Atlantic for Spain. Of the four ships that left Spain, only one, the Santa Maria del Espinar, limped into the Spanish port of Seville. This was on July 22, 1530. Amongst the passengers were 60 or so captive natives he had purchased from the Portuguese in Brazil, which also included women. These were sold into slavery in Seville becoming the only “valuable asset” Cabot brought back from expedition.

Back in Spain

His trip into the interior of South America was a disaster, although he managed to found a few settlements, including Sancti Spiritu. But the legend of the fabled riches was never found although it led to continued exploration of the interior and eventually lead to the founding of the Spanish-speaking state of Argentina.

In Seville he would stand trial for abandoning some of his men to their fate, as well as his failure to keep to his mission. He squandered Spanish wealth and behaved poorly towards his crew including bullying and in one case the violent death of two sailors on his orders.

He would be fined and banished to a penal colony in Africa for four years. But Charles V was out of Spain at this time and when he returned, the King commuted the sentence of exile, although the fines were paid. He was stripped of his office of Pilot-Major for a time, but was able resume his office.

However, before resuming his position, Cabot departed for England in 1548. Now in his 70s, he was offered a naval position by King Edward VI as governor of the Muscovy Company. In this position he managed to establish English trade with Russia.

This would be his last role as he died most likely in 1557, but not before publishing his famous planisphere in 1553.

Cabot lived through turbulent times for both England and Spain. His life in England spanned the reigns of King Henry VII to Queen Mary. He lived in Spain under Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and during most of the reign of the English king Henry VIII. Cabot was in England during the short reign of Edward VI but also saw the savage repression under Queen Mary, although as Catholic he wasn’t under any threat.

By his death in 1557, Europe was in an upheaval. The Catholic Church splintered throughout Europe, Peasants waged wars against noblemen in Germany and Catholic forces persecuted Protestants in France and elsewhere. As for Canada, it had become the nominal territory of the French and Basque fishermen. The St. Lawrence Iroquois disappeared and the Innu and Algonquin natives inherited their lost territory.

Scoundrel, genius or both?

We come to the crux of the matter. Was Sebastian Cabot a scoundrel, a genius or both? I think he was both. He didn’t possess the honesty and integrity of his father. He was able through flattery and exaggeration to access the most powerful people in Europe during the first half of the 16th century. His two voyages, one to the far north for the English and the other to the far south for Spain, didn’t achieve much of value for the respective monarchs. They did result in the first exploration of parts of the Hudson’s Straight and the first exploration of deep within the La Plata basin. Sebastian Cabot survived both expeditions but his survival instincts came at the cost of the lives and well-being of others, to say nothing of their money.

Compared to his contemporaries, Cabot’s achievements were mediocre. He lived off the name of his father, so much so that he took to himself his father’s achievements. He learned enough about navigation and sailing to be dangerous to others. The constant mutinies against his leadership spoke volumes about his character and capabilities, although he wasn’t afraid of a fight. He showed flashes of genius but the scoundrel in him overshadowed those wins.

Of all the explorers I’ve written about so far, Sebastian Cabot showed that even in the great Age of Exploration, scoundrels could assume the highest offices. He might have been a genius at some level but he was too self-interested to know better. In the end we are left with a mixed view of someone who could have done so much better.

Further reading

Henry Harrisse, John Cabot, the Discoverer of North-America and Sebastian, his Son (London, 1896), pp. 115–25.

CABOT, SEBASTIAN, Italian explorer and cosmographer; son of John Cabot; leader of an expedition for discovery of a northwest passage, 1508–9; d. 1557.

James A. Williamson, The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII (Hakluyt Society, 2nd Series no 120, 1962), pp. 33-6

Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol's Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, 23 Nov 2016), ISBN 0995619301, 104 pp., 71 illustrations, £11.99 rrp.

Harrisse H., John Cabot, the Discoverer of North-America and Sebastian, his Son (London, 1896). 115.

Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon. Cabot and Bristol's Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol. 64.

Harrisse H. 185.

Harrisse H. 205.

FOUNDATION of São Vicente. In: Itaú Cultural ENCYCLOPEDIA of Brazilian Art and Culture. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2024. Available at: https://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/obras/86579-fundacao-de-sao-vicente . Accessed on: December 15, 2024. Encyclopedia entry. ISBN: 978-85-7979-060-7